Search the latest and greatest job opportunities in sport

2019 has been quite a year for Women's football and one that will likely define it's future growth as the women's game looks set to take advantage of the boost from the FIFA World Cup in France 2019, which registered audiences of millions, to intensify their demands in their fight toward the professionalisation of women’s football.

2019 has been quite a year for Women's football and one that will likely define it's future growth as the women's game looks set to take advantage of the boost from the FIFA World Cup in France 2019, which registered audiences of millions, to intensify their demands in their fight toward the professionalisation of women’s football.

image credit: Lorie Shaull.

Women’s football will remember the FIFA Women’s World Cup France 2019 as the most important in its history to date. For the first time, there were over one billion viewers in 206 countries and over a million tickets were sold, with the average stadium attendance exceeding 75%. Not even the most optimistic FIFA predictions pointed to such figures. But it has taken eight editions of the World Cup for women’s football to really manage to claim its own place. Some will think it is a short time; its protagonists, however, believe that it is enough. The conquest of rights is not a matter of faith in women’s football; it is a constant contribution of solid arguments in that struggle toward professionalisation.

And in that way, there are implicit protests and sacrifices in pursuit of a better future. The FIFA Women’s World Cup France 2019 did not have among its protagonists the woman who won the first Golden Ball in the history of women’s football in 2018, a distinction that has been awarded in the men’s game since 1959 at the initiative of the magazine France Football. The Norwegian Ada Hegerberg refused to play in the World Cup, considering it to be the best way to denounce the discrimination still present in women’s football. In her acceptance speech in front of the top leaders and protagonists of this sport, Ada thanked “my colleagues in Lyon because without them this would not have been possible, and France Football for the initiative. And to the youngsters, I tell you to believe in yourselves,” said the player that has reached the highest level at only 23 years of age.

Megan Rapinoe, the biggest star of the four-time world champions team of the United States, and winner of FIFA’s ‘The Best 2019’ award for the best women’s player of the year, also took advantage of that platform to send a message to the world. “We need a real change. If everybody was equally outraged about the lack of equal pay or lack of investment in the women’s game other than just women, that would be the most inspiring thing,” said Megan. “We have a great opportunity as professional football players, we have so much financial success, financial and otherwise, a huge visibility, and we have a unique opportunity in football different to any other sport to use this beautiful game to actually change the world for better. It’s what I ask everyone. I hope you take it to heart and do something. We have incredible power in this room.”

Women’s football continues to grow in double digits in popularity, and the money is coming, albeit in dribs and drabs. Despite the attention it captures, it is a sport still in development. Television coverage, essential to attract new sponsors to the stage, is beginning to happen. Historically, sponsorships of women’s teams or the sale of television rights for tournaments were part of larger packages with their male equivalent. Currently, according to Deloitte, about 60% of women’s football teams in major leagues around the world have a different sponsor on their shirts than the men’s teams.

Visa, in a change of its sponsorship strategy, has also decided to take a step forward and invest the same amount—$30 million—in the promotion of the Women’s World Cup as in the men’s. “We may not recover it immediately in terms of ROI, but ours is a long-term commitment,” says Stephen Day, director of sponsorship in Europe.

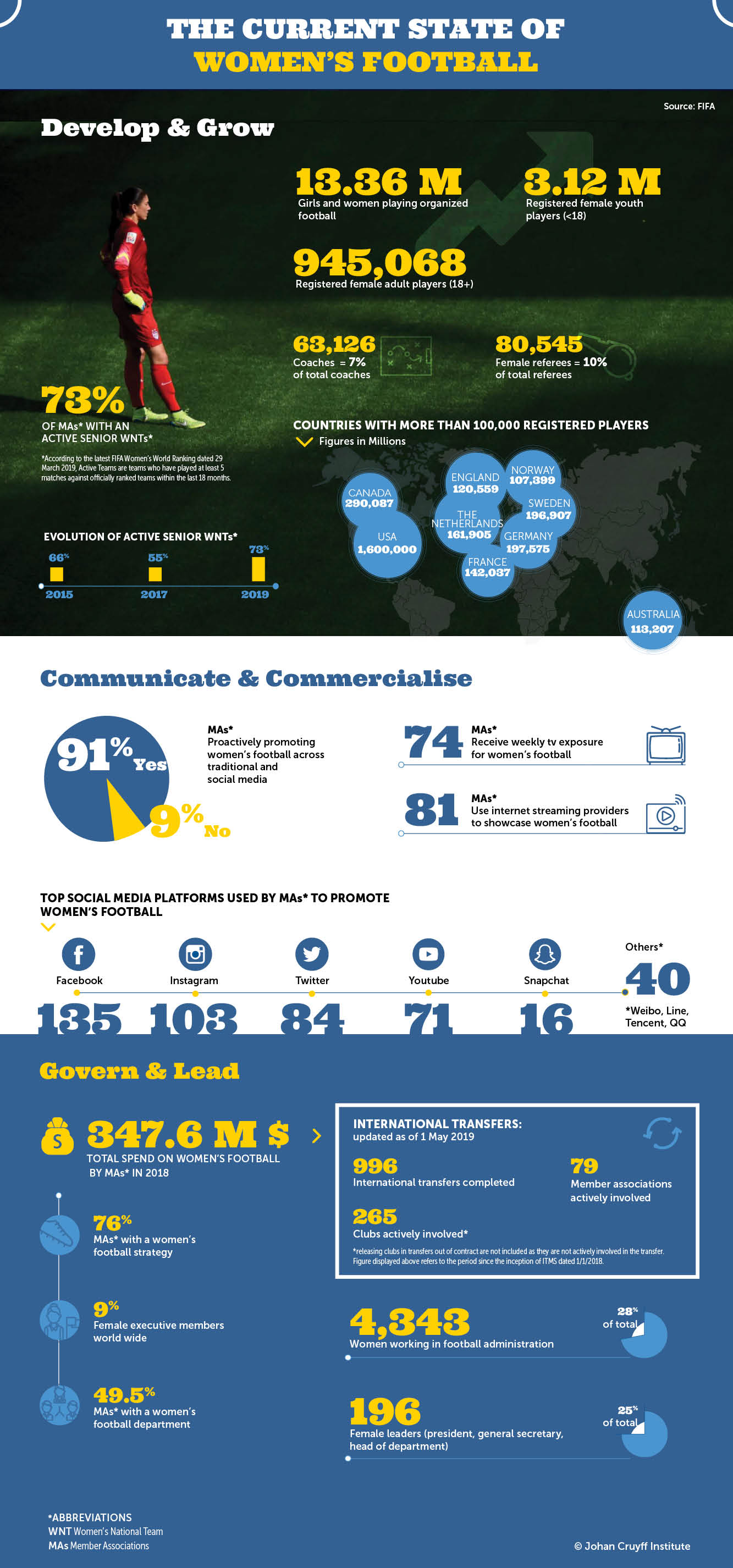

FIFA estimates that currently 30 million women play football in 180 countries, a figure that has increased fivefold since 1985, and has the stated goal of increasing that number to 60 million by 2026. Of these 30 million, some 5 million are registered nationally. The question is, in what conditions? When we talk about professionals or semi-professionals, the figures go down alarmingly: only 3,600 players can live from football at European level, according to The Economist.

FIFPro data reveals that the average salary of a professional female footballer amounts to €8,162 per year. In the English Women’s Super League (WSL), one of the richest competitions in women’s football, the average annual salary in 2018 was €31,400, just one hundredth of what an ‘average’ male professional player can pocket per season. According to Forbes, the best paid athlete in the world in 2019 is Leonel Messi, with an income of $127 million ($92 million in salary and bonuses and $35 million in endorsment and sponsorship agreements). Ada Hegerberg, the world’s highest paid female footballer, earns €400,000 a year.

Several decades of difference separates men’s and women’s football: specifically, 61 years passed between the first edition of the FIFA World Cup for men (1930) and for women (1991); and 46 years between the first UEFA Champions League for men (1955) and for women (2001). Many generations that affect growth, development, infrastructure, investment and income. Two worlds of the same sport.

“I think that right now there is the perception that women’s football only costs money and the first step toward the commercialisation of women’s football is to change that mentality,” explains FIFA’s director of women’s football, Sarai Bareman. She believes that “many people involved in the governance of football still consider that men’s and women’s football are the same, but there is a historical gap between the men’s and women’s game that we cannot ignore, so we cannot expect the same results.”

The differences in the remuneration for winning the same competition are also abysmal. The prize money that the women’s team of the United States received as champions of the World Cup France 2019 was $4 million, while the French men’s team that won the 2018 World Cup in Russia received $38 million. The comparison in the UEFA Champions League is even more scandalous: €20,000 of revenue for each qualifying round (an amount that, according to the clubs, does not even cover the travel costs) and €250,000 for the winners of the Women’s Champions League. In the men’s competition, a team gets €2.7 million for each match won in the group stage and €900,000 for a draw. That means that a team could win €82.4 million if it were to win the Champions League having won all the matches.

The governing bodies of women’s football have drawn up their roadmap for the coming years. Both FIFA and UEFA have taken on the commitment to lay a solid foundation for women’s football to continue to thrive.

‘Dare to shine’, the slogan that FIFA chose for the last Women’s World Cup was an omen. The girls shone and now that they have the attention of fans and the media they want to take advantage of the demand to consolidate results and move toward professionalisation. It may take another decade for women to be able to consider football as a full-time and well-paid profession. We will have to wait until 2026 to see if those who have the power today to force change have done their homework well.

This article was originally published by our partner The Johan Cruyff Institute and can be view here.

Search the latest and greatest job opportunities in sport

In the world of professional sports, sponsorship represents a significant source of revenue and plays a vital role for t...

Read moreThe sports industry is a vibrant and multifaceted industry, made up of a diverse range of sectors that shape its global ...

Read morePablo Romero, director of protocol at Sevilla FC and lecturer in the UCAM Master's Degree in Sports Management, shares t...

Read more