Search the latest and greatest job opportunities in sport

‘Olympic sports urged to be less entitled, more business-like,’ ran the Washington Post’s headline in March relating to ASOIF’s far-reaching new report, ‘Future of Global Sport’. Was it accurate, Sportcal ask ASOIF’s Andrew Ryan?

‘Olympic sports urged to be less entitled, more business-like,’ ran the Washington Post’s headline in March relating to ASOIF’s far-reaching new report, ‘Future of Global Sport’. Was it accurate, Sportcal ask ASOIF’s Andrew Ryan?

The ‘Future of Global Sport’, a report published last week by the Association of Summer Olympic International Federations, had its genesis at the end of 2017, and began with the question: “Is there a point to an international federation?”

This was, unsurprisingly, regarded as a radical question for ASOIF, an umbrella body of international federations, to ask itself, Andrew Ryan, ASOIF’s executive director, tells Sportcal Insight. However, he continues, “we realised the world is changing very fast and we didn’t have a clear view of the future landscape of sport.

“It started as an internal project, but as people heard about it they approached us and wanted to help [the report is based on interviews with leading figures in the areas of sport, business and public authorities, including the IOC’s Christophe Dubi, Facebook’s Peter Hutton, Olympic Broadcasting Services’ Yannis Exarchos, chair of the European Commission Expert Group on Good Governance Darren Bailey and former IOC marketing director Michael Payne].

“On the other side, there was demand from international federations for access, so we began to invest money into it. It’s poignant now, for obvious reasons, because every day there’s a story related to [the themes of] the report, whether in rugby [controversy over a proposed new World League], or FINA [the world governing body of swimming’s attempts to stave off the rise of a new commercial competition, the International Swimming League].”

The answer to the question of whether there is a point to international federations, quickly became apparent, Ryan says, and it was “universally the business side of things that gave the answers: someone has to manage the rules and make sure the same rules are used globally.

“Then the public authorities say that they can only work within national or geographical groupings. They’re not global. They can’t handle cross-border issues like illegal betting. It’s all stuff that no one else wanted to do, like managing the calendar. The key one of that list, without question, that kept on coming up, was that someone has to co-ordinate the development of athletes. Business won’t do it, because of the impact on its bottom line. It only wants to work with elite athletes.

“That means that someone has to pay for junior events. The key thing is to run a global development programme, co-ordinating the things that national governments put in. The business world in every sport requires high-level athletes from all parts of the world. As soon as India, for example, doesn’t have top athletes, it can’t sell TV rights.”

All this raises the question of how sports, through their national federations, will pay for the development programmes that business won’t touch. The report’s answer, Ryan says, is that, “They have to be entrepreneurial’; they can’t be as amateur as in the past. They will have to develop agreements between public and sports governing authorities without breaking antitrust laws.

“It’s no longer acceptable for an international federation to tell athletes they can’t compete in any other events. A mechanism is being worked out for that in Europe. Clever work is being done, so that if a commercial entity wants to operate an event, a certain part of the revenues needs to go to the international federations. After all, someone has run the anti-doping programme, provide medical services, train referees…”

One of the report’s most arresting quotes comes from Simon Morton, the chief operating officer of UK Sport, the national sports administration and funding body, who says: “If NFs [national federations] and IFs don’t assert themselves, then business will naturally move in.

“They have to think more like businesses. A protectionist approach is not going to provide a solution. Federations cannot rely on a historical entitlement to regulate sport simply because they have a wider social objective. Their leadership position has to be earned in the face of commercial challenge.”

In a section on the future of sports, the report predicts that a trend for private businesses to surpass international federations in exploiting sporting properties commercially is only set to continue in the next 20 years. As a result, federations will be forced to re-evaluate their role and strategies in favour of partnering and collaborating with the private sector.

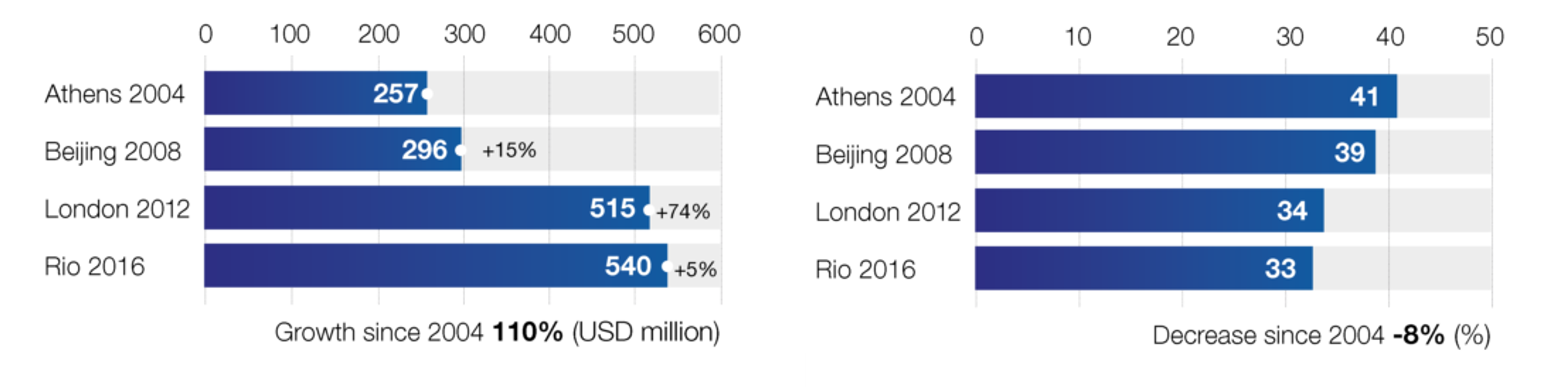

The point is illustrated with a chart showing that about half of summer Olympic federations have a “significant reliance” on International Olympic Committee revenues (more than 25 per cent of their revenues comes from this source in a four-year Olympic cycle), while more than a third rely on Olympic revenues for over 45 per cent of their income. Although this reliance is declining, the bottom third of the federations are sternly warned that they would be “ill-advised to let this situation linger.”

ASOIF IF dependence on Olympic Revenues (collective evolution). Source: ASOIF

Despite predicting that “‘live broadcast’, whether traditional or digital, will continue to play a significant role in most sports’ commercial strategies,” the report points out that viewers are increasingly likely to use D2C (direct-to-consumer), OTT platforms and social channels to keep up to date. It cites a figure from eMarketer of 765 million people using an OTT subscription at least once a month in 2018, in a market that is estimated by PwC to be worth $45.4 billion.

Ryan says: “The value in future is the number of fans that you engage with. But it’s not just that. We see a big change coming. It’s no longer about how many hits, it’s about how much data about your fans you have that enables you to make predictions about their behaviour. Why are they tuning in?”

Meanwhile, in a section entitled ‘A future for multi-sport mega-events’, the report points to the problems the IOC has experienced in attracting competitive bid processes for recent editions of the Olympic Games, and argues that “the prevailing view seems to be that everyone wants to watch the games but nobody wants to organise or pay for them any more.

“This has pushed the IOC into elaborating ‘The New Norm’ concept, adding to the earlier introduction of its ‘Agenda 2020’, a set of 118 reforms that re-imagines how the games are delivered.”

The problem is not confined to the IOC and the Olympics, Ryan says, pointing out that international federations have tended to adopt an “arrogant position” with respect to finding hosts for their events, typically issuing an invitation to cities or national federations and waiting for the bids to roll in. “Luckily,” he says, “those days seem to be over. The future is more in line with the Glasgow-Berlin model [of hosting last year’s inaugural, multi-sports European Championships] - trying to co-operate and create a balanced share of risk between the parties, who are in it together.”

The report makes 10 recommendations which, it says, offer “a blueprint for IFs to adapt and take advantage of the opportunities presented by today’s increasingly disrupted and competitive landscape.” The recommendations are divided equally under the headings of ‘Governance’ and ‘Entrepreneurialism’:

Explaining the concept of ‘fast failure’, Ryan says: “How does business today work? It takes risks and experiments by empowering younger people to try and do stuff, but in a short-term way. It accepts that a lot of initiatives might fail. In sport, there’s a paranoid fear of failure. There’s always the next general assembly when you’re going to have to explain what went wrong.”

So, what about that provocative Washington Post headline: 'Olympic sports urged to be less entitled, more business-like'. Was it accurate?

“There is a sense that there’s been an assumption of international federations that they are the custodians of sports, even to the exclusion of other people,” Ryan replies. “If a sport doesn’t have money attached, that’s been easy to do because, to be brutal, no one else is interested.

“But the report is saying – and this is not ASOIF speaking, we commissioned it to get an idea of what other people thought was going on – that IFs can no longer rely on being the custodians. They have to earn the entitlement to behave autonomously and have Europe respect the European model of sport and the specificity of sport.”

Sounds like the headline was pretty much spot on.

To read the report, click here.

This article was written by Callum Murray and originally published by our partner Sportscal. You can read the original article here.

Search the latest and greatest job opportunities in sport

In the world of professional sports, sponsorship represents a significant source of revenue and plays a vital role for t...

Read moreThe sports industry is a vibrant and multifaceted industry, made up of a diverse range of sectors that shape its global ...

Read morePablo Romero, director of protocol at Sevilla FC and lecturer in the UCAM Master's Degree in Sports Management, shares t...

Read more