Search the latest and greatest job opportunities in sport

First Published on Soccerex

Consider two scenes of British sporting officialdom, spaced a single late winter week apart. The first is an example of authority as a sequence of structure and sense, the second of haplessness too formless to constitute farce.

In the final round of fixtures in this year’s Six Nations rugby championship the Scottish full-back Stuart Hogg chases forlornly after a loose ball, coming up well short and smashing into his Welsh opponent Dan Biggar. Referee Jerome Garces brandishes a yellow card to send Hogg for a ten-minute term in the sin bin. Then, seeing a replay on a Millennium Stadium screen, Garces realises the collision is more dangerous than first thought. He runs to the touchline and pulls out another card, this time a red one. Hogg’s tournament is over.

Seven days later in London, on 22nd March, Arsenal’s springtime thaw has lapsed into meltdown. Less than 15 minutes into a Stamford Bridge encounter with Premier League title rivals Chelsea, the Gunners are two goals down and already facing humiliation when the home side pour again into their penalty area. Eden Hazard shoots, midfielder Alex Oxlade-Chamberlain goes to save on the line with his head and then, as the ball curls wide, his hand. Referee Andre Marriner points to the spot and produces a red card. It is an error – by strict definition, Oxlade-Chamberlain has only committed a bookable offence. But no matter: inexplicably, the card has been shown to the Arsenal left-back, Kieran Gibbs, who was stationed five yards away.

The two incidents seem to bear a simple lesson. By the time Gibbs had made his way within swearing distance of the tunnel, the briefest TV replay had confirmed a staggering case of mistaken identity. An official acting on this may not have spared Arsenal their 6-0 thumping but with millions watching, millions wagered, and millions spent, events would at least take the proper course. Surely soccer’s Ludditism would have to end. Wouldn’t it?

On the Monday morning after Marriner had spied his albatross – somewhere between the transmogrification of the error into internet meme and the suitably absurdist coda, where England’s Football Association eschewed suspensions for all involved – Germany’s Bundesliga clubs were given the chance to bring technology into on-field affairs. They passed it up. Nine clubs in the top division and 15 in the second voted against the introduction of the sort of goal-line systems in use in the Premier League and this summer’s Fifa World Cup, leaving the proposal well short of the two-thirds majority required.

The naysayers’ opposition was predicated on that most German of instincts, pragmatism, with the €500,000 cost per club of the GoalControl system over three years not deemed to offer adequate benefit. “We debate over one, two or three decisions in a season,” said Hamburg managing director Oliver Kreuzer. “Sometimes you are on the right end of things, sometimes not. It evens out. On the other side, you have extreme costs. It doesn’t pay off.”

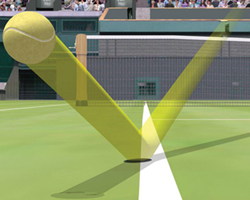

Goal-line technology is unusual in that it has been built to order. In other sports, much of the support available to officials – either through video replays or aids from companies like Hawk-Eye – is derived from broadcast tools. It is instructive, too, to see how these are used.

Tennis and international cricket have both allotted decision reviews to players for several years. To a greater or lesser extent, both work – in the sense that they reduce the number of incorrect decisions that are allowed to stand. But without getting too invested in their micro-legal aspects – the fundamental challenge to the ultimate authority of the umpire – it can be argued that they do not guarantee a fairer game. Instead, as incorrect referrals are spent, they add another element of games-playing.

Of course, matches in which every decision could be reviewed would be borderline unwatchable, as the International Cricket Council discovered when it first trialled a scheme which gave umpires unfettered access to technological aids in 2005. Its Super Test between Australia and a World XI ran two days short of its allotted six, but it felt a good deal longer.

It is for similar reasons that, by Fifa mandate, any licensed goal-line technology must be able to produce a decision in under a second. Yet the logical conclusion in all of this is that it is not the integrity of the sport that is being protected, but the integrity of the broadcast.

There is nothing inherently wrong with that and in most cases, current systems will lead to better ones. Still, it does suggest that the interests of sporting authorities are not entirely motivated by a hunger for justice – and that is hardly inconsistent with the norm. From illegal simulation to illicit stimulation, the appetite for crusades at the top has often been proportional to the threat to the spectacle.

Technology will undoubtedly play a growing role in officiating top-level sport but it will not solve everything. Uefa’s new communications man, Pedro Pinto, went straight to Twitter to argue that the five-referee pet project of president Michel Platini would have prevented a calamity such as the Gibbs dismissal. That may or may not be so; what is true is that Platini’s scheme is an actual attempt to address refereeing standards, rather than apply a high-tech coat of heavy emulsion.

Another look at the actions of Garces and Marriner reveals something else. The former is decisive in the first instance, and again on realising his error. His calls go uncontested by either set of players. The same is not true in the latter case, and that cannot solely be explained by the use of video.

There is more than one aspect to a modern approach.

Eoin Connolly is the Editor of SoccerexPro Magazine

Search the latest and greatest job opportunities in sport

One of the many key success factors when assessing the quality of degree programmes is the employability rate of its gra...

Read moreThe global major event industry is one of the most thrilling and impactful career paths you can choose. If you’re lookin...

Read moreStarting his career in New Zealand within sports events, Regan gained valuable experience with Hockey New Zealand and Ne...

Read more